Naked truth and children from the camp are the hardest part of "Diary of Diana Budisavljevic"

Dana Budisavljevic, the director of "The Diary of Diana Budisavljevic," didn't make up her little girl in a red coat. The voices of all the girls, who escaped the fate of those depicted by Spielberg, could be heard long before and after Schindler's List came out.

Completely sincerely, devoid of any vanity, Dana gave a voice to the girls and boys who had not been heard in these 70 years or so, and who, although they did not get coats in the camp, did get a chance to grow up. Thanks to Diana Budisavljevic, another woman who was unjustly never mentioned.

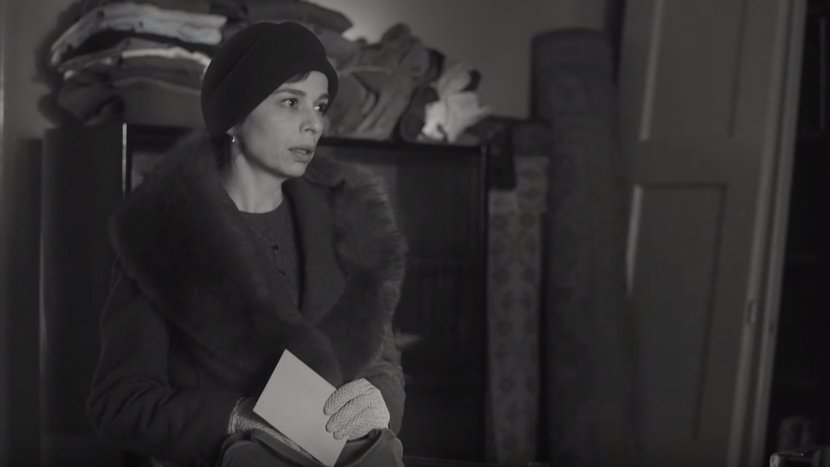

Diana herself speaks through Dana's film. Measured, quiet and rare. Without many words and color, "The Diary of Diana Budisavljevic" is reminiscent of a photo album into which Diana draws crosses next to the deceased children, too young to know who they were and where they came from. The only thing that was known about them was the thing that had sentenced them to starvation and illness - they were Orthodox Christians.

However, this was not discussed about after the war. Like about the NDH (Independent State of Croatia), the movie has nothing nice to say about the regime that came after it. In the former, Diana was rescuing quietly, in the latter she was left to silence, along with all the children that she saved.

This film is therefore most striking when the naked truth gets a chance to speak for itself. When the testimonies of four adults who ended up in Jasenovac, Gradiska and Loborgrad as children, (it was high time) end the illusion.

"We were all lying here by the wall, with no underwear. Our colons were protruding, flies all over them. If these walls could speak, what a horror they would tell," says Zorka as she peels the dried paint off a wall in Jasenovac.

"My last name was 112," Zivko sums up the unsuccessful quest to find out where, and from whom he came from in these five words.

Milorad's jaw trembles when he talks about his sister, from whom he was separated in front of Gradiska's gates. He never found her again.

"On the 70th anniversary of my family's tragedy, we finally said goodbye to her. We said, 'We don't know where your grave is, but now you're among your people'," he says.

The climax of the film is again the truth made bare - archival footage showing real Diana and half-naked, skeleton-like children, too scared to react to the camera, too weak to defend against swarms of flies covering them.

"This time we only took those children who could stand up. It turns out that the sick ones do not survive the noon," Diana was honest about her second return to Gradiska.

This film is also honest. It contains no fabrications, no accusations, no assumptions. The film is so honest that we only hear the voice from the diary when we get to the war moment in which Diana really started writing it. It doesn't lie to portray Diana herself as a fighting heroine who avoids danger by the split second, because we are used to having courage look like that. She didn't want to be a hero. Heroism chose her when all she did was try to to hand over aid for the Orthodox in the camp. Then to send them warm clothes... onions, carrots and sugar. Not to close her eyes before the crime. To find out where the children are... Card by card, with pencil and ink, she saved almost 10,000 souls.

And to immediately answer the questions that will inevitably be asked - this film does not hide the criminal past of (NDH leader) Pavelic and his entourage, it doesn't hide the enthusiasm for Nazism in Zagreb, it doesn't hide that the Ustashas operated the camps, it doesn't hide the terrible conditions in them, the scraps and corn seeds they fed the children with. It doesn't hide, either, the attention nor the love with which some Croatian families accepted and cared for the Serb children until the end of the war. The humanity of individuals and their willingness to earnestly fulfill their, as they say in the film, Christian duty in dangerous times are not hidden, which was also the loudest silent cry against Nazism.

The other questions that Diana herself asked remain: Where did all these children end up? Why were healthy Serb boys "clad in Ustasha uniforms," what happened to them? What happened to Diana's archive seized by the Communists?

But this has only started to be talked about...

Truth pulled from the depths of time

"On this occasion I would like to thank posthumously Diana Budisavljevic on behalf of all the children she rescued from the camp. And the biggest gratitude is given by this film, which has pulled from the depths of time a humane story, that had been doomed to oblivion. Although denied by the ones and the others, the truth has won. Here, we are witnesses to that truth. And well done to Diana and to the truth," Nada Vlaisavljevic, one of the survivors of the Loborgrad camp, said in front of the numerous audience at the Free Zone festival last night.

"The Diary of Diana Budisavljevic" will be shown in cinemas across Serbia starting Thursday, November 14.

Video: Ustashas snatched him from his mother when he was 2 years old, Diana Budisavljevic saved him from death

(D.D.S.)

Video: Zafranović: David je ostavio veliki trag u srpskoj kinematografiji

Telegraf.rs zadržava sva prava nad sadržajem. Za preuzimanje sadržaja pogledajte uputstva na stranici Uslovi korišćenja.